“The Proud City” is a wonderful bit of film freely available on the Internet Archive. Made to sell the idea of the Abercrombie plan for London, it is passionate about the need to tackle the unsanitary conditions in which much of London’s inhabitants were forced to live, and about the benefits to all of a planned city where transport moved freely, where children had somewhere to play, and where ‘communities’ would thrive and develop. It also provides a great window onto the people and the landscapes of wartime London. I especially like the ‘men from the ministry’ types in their hats and three piece suits clambering over rubble and into living rooms, tape measures in hand.

The Abercrombie Plan (more accurately ’plans’ – there was the County Of London plan of 1943 and the Greater London plan of 1944) has its roots pre-war, but the same thinking behind the 1941 Beveridge report into social security – that common sacrifice in wartime should result in common benefits in victory – provided a catalyst for the Plan to be drawn up. And like Beveridge, who fought against the five evils of squalor, want, ignorance, idleness and disease, the Abercrombie plan set out to tackle London’s own miseries of “decay, dirt and inefficiency”.

(As an aside, you have to feel sorry for Abercrombie’s co-author, J H Forshaw. Although Abercrombie was the main author and driver behind the plan, Forshaw seems to have been almost entirely forgotten. This blog post will do little to rectify that – I am using ‘Abercrombie’ as a name for the plan itself.)

Further impetus was of course given by the fact that there was almost literally a clean slate where the Blitz had razed whole areas (50,000 homes in inner London were destroyed, over 60,000 in outer London); across the city as a whole over 2 million properties had suffered some bomb damage. In its scale Abercrombie is similar to the plans drawn up the previous time large areas of the old city needed to be redeveloped, after the Great Fire, with Sir John Evelyn’s plans and Wren’s vision of the City both giving long, wide, straight roads linking new urban spaces.

Certainly, the scale and ambition of the Plan would have had no hope of even being considered had not wartime devastation meant that some form of citywide reconstruction had to happen; the Plan prescribed widened roads, factories to be moved, new housing to be built around new public green spaces and the resettlement out of the city of a huge number of the current population. And this wouldn’t just be new build on bombsites as thousands of surviving buildings would need to be cleared to make way for the vision.

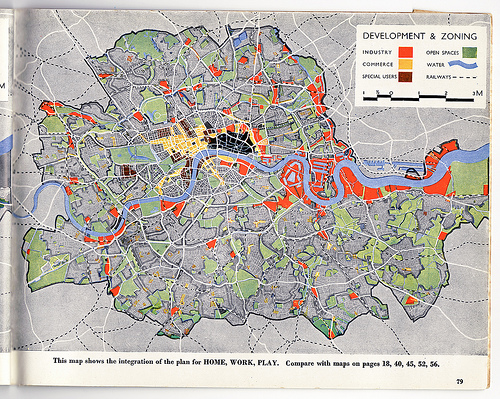

The intentions behind the plan were almost entirely noble, one of the main ones being to reduce overcrowding. There would be an inner and an outer green belt on which no further development would be permitted; the boundary of ‘London’ would be permanently fixed. Because London was projected to carry on growing – it was already the biggest city in the world – the Abercrombie plan involved moving up to a million inhabitants to ‘new towns’ up to 50 miles from the centre. These would be developed to provide decent housing and industrial areas so that the population of these towns would be self-contained and not have to commute back into London. This migration would clear space for redevelopment within the city so that newer houses – terraces and tower blocks – could be built with green space around them. Development would be ‘zoned’, with industrial and residential areas separated, so that homes were no longer pressed up against factories.

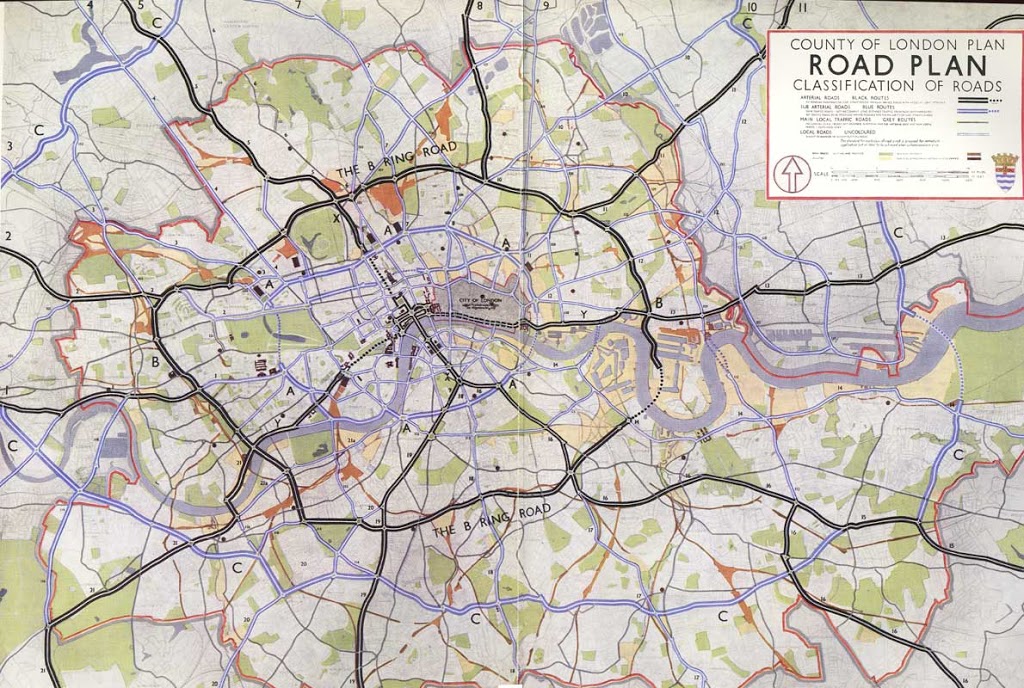

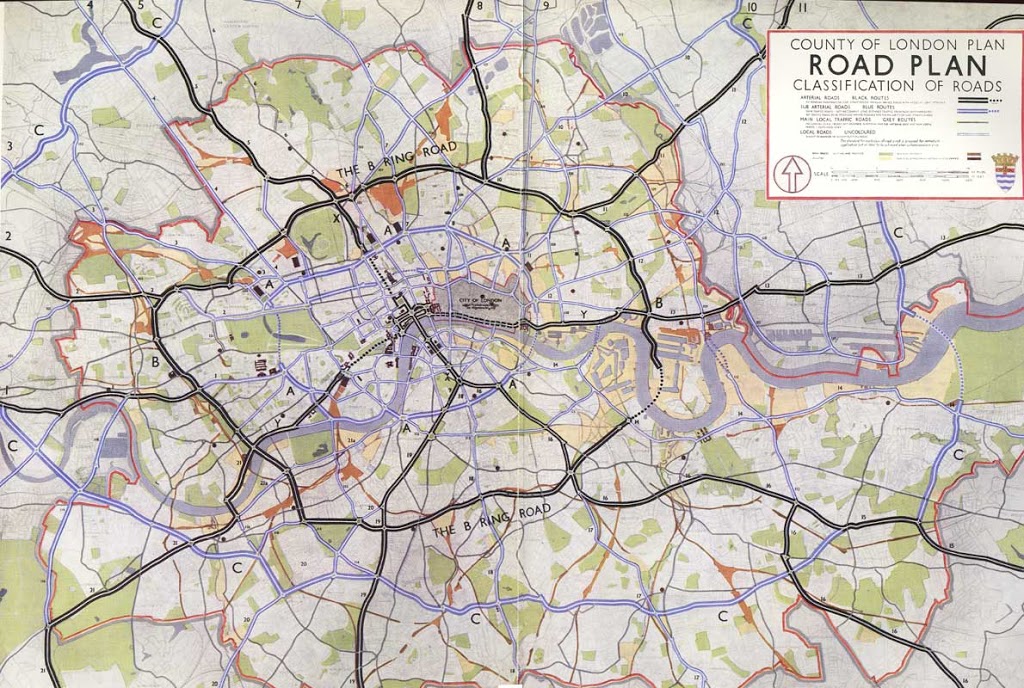

Other major parts of the plan were to do with transport and the flow of traffic, a cause of complaint to Londoners since at least the seventeenth century. Abercrombie identifies three issues – traffic coming into the city, traffic passing through the city, and local travel. The Plan addresses these with ten major arterial roads linking London with other cities, and six ‘ring roads’ at various distances from the centre. Fast through traffic can skirt the middle of the city, and local traffic can move around the rings without interfering with arterial roads. These arteries would be six lane motorways (Abercrombie was very taken with US highways) lined with trees on wide verges, and with green central reservations, with huge intersections to keep the traffic moving freely.

The overarching idea of the Abercrombie vision was of London as a collection of communities. As London had grown it had swallowed up outlying villages and towns, yet the spirit of the old village communities seemed to Abercrombie to have survived. The plan wanted to build and expand on these communities; local areas would have schools and shopping parades, collections of these neighbourhoods would form larger areas that had health centres, cinemas, hospitals, civic amenities, concert halls (!), larger shopping areas and so on. In all cases population density would be controlled and there would be a fixed proportion of green space within each area.

Rail is mentioned almost parenthetically in the film. Against pictures of dirty steam trains on viaducts cutting through residential areas one of the planners talks about the need to ‘tidy up’ the railways, to electrify the trains and build tunnels to take them into the central stations. This would free up land for more of the development plans. One senses that the cost of this hadn’t been too closely investigated.

Despite the best efforts of the film, and the vision it created, most of the Abercrombie plan failed to make it from the discussion stage. Obviously the costs involved would have been immense and post-War Britain was in no position to afford development on such huge scale, but perhaps the main reason for the failure of the grand plan was that it viewed London as a problem that needed a solution. Where grand visions for London fall down is in their view of a city as something ‘manageable’, that it is some sort of machine that can be controlled by an overseer, with a predictable cause and effect from any changes. Somehow order can be imposed if only the vision is big enough and the action drastic enough.

“It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that much of the planners’ project was misconceived… imposing one man’s vision of order on the chaotic, ancient, changeling, untameable disorder of London” Jerry White, London in the 20th Century

London, like all cities, is more of an organism, a thing that grows and develops to adapt to change and, as such, much less mechanistic and more unpredictable than visionaries permit.

If you want a hint of how London might have been had Abercrombie’s plans been fully introduced, visit some of the post-war new towns that were built. I leave it up to you to decide whether London would have been better off had Lambeth, Poplar, Southwark, Stepney and the rest been rebuilt along the lines of Harlow, Hatfield, Bracknell or Stevenage.

And, as Peter Ackroyd points out, one of the ironies of the plan was that “instead of restricting the size of the city, the planners immeasurably expanded it….The ‘new towns’ ineluctably became as much a part of London [as Bloomsbury and Covent Garden]..so that the whole south eastern area became ‘London’”.

See also my post on the precursor to Abercrombie, the London Society’s Development Plan for Greater London 1914-18

Links: