Back in the British Museum for the first time since lockdown and prepping for a real life tour with a real life guest.

The Standard of Ur is an object I’ve walked past on numerous occasions, but until yesterday hadn’t ever really spent any time looking at. Its history and what it tells us about early city civilisations is remarkable.

It was discovered in the late 1920s during the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley’s excavation of the city of Ur. One of the most famous and earliest of the cities of ancient Mesopotamia (“between the rivers” of the Tigris and Euphrates; modern-day Iraq), Ur was a city-state of the Sumerians, founded about 3800 BCE.

During his excavations, Woolley came across what he thought might be a standard, a board or plaque carried in front of an army. Although this theory was rapidly discounted, the name has stuck.

The ‘Standard’ is a small box, tapering towards the top (a narrow trapezoidal prism if you like) that is about 22cm high and 50cm wide. It is dated to between 2600-2400 BCE.

Originally of wood, it is decorated with inlays of shells, lapis lazuli and red marble on a bitumen base (shells from the Gulf, lapis from Afghanistan, marble from India, which shows the travelling or trade routes of the ancient Sumerians).

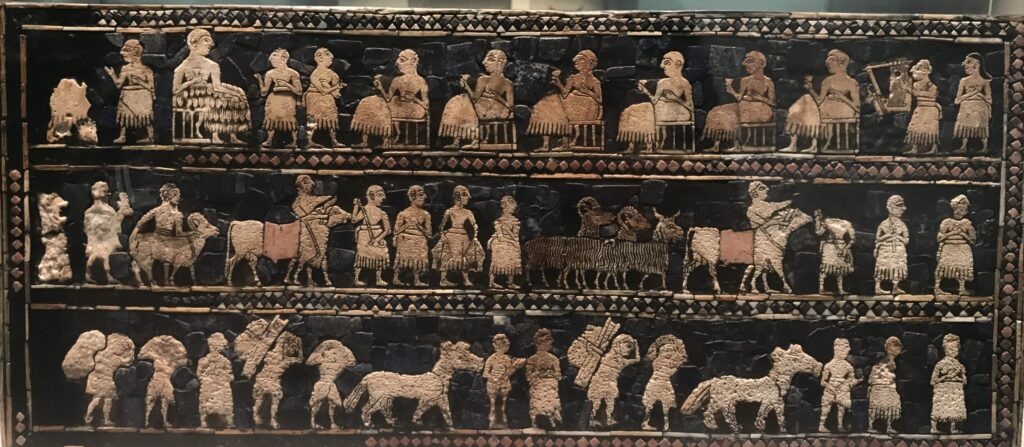

The two main faces are split into three panels of ‘illustrations’, one side depicting “peace”: the king (bigger than anyone else – the Sumerian name for a ruler translates literally as “the big man”) drinking with six other seated figures while being waited on by attendants. There is someone playing a lyre (also found in Ur graves) and someone else perhaps singing. The two panels below this seem to show people bringing tributes or taxes – animals, fish, sacks from harvest.

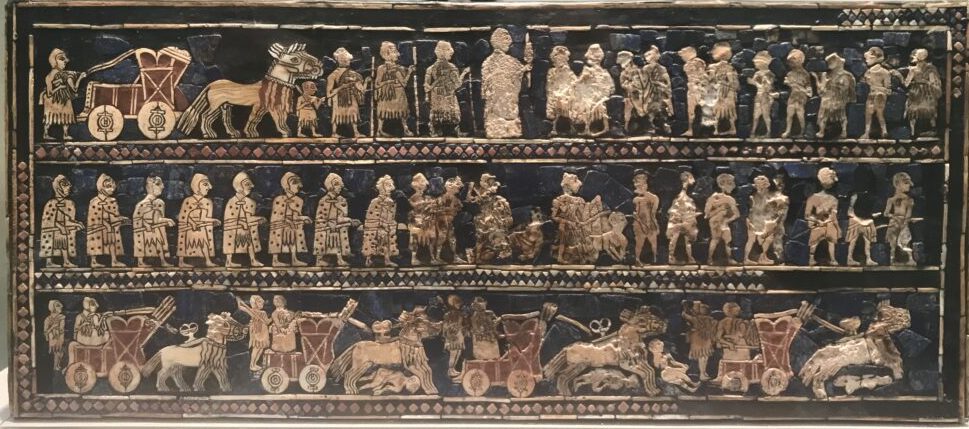

The other side shows “war” (visible at the top of this page). In the top panel the king stands at the head of soldiers and a war chariot as prisoners (stripped naked to show their utter defeat) are paraded before him. In the panel below is a column of soldiers/warriors in cloaks and helmets, carrying spears, with more of their enemies being killed or driven in front of them. The bottom panel shows a Sumerian four-wheeled war chariot in four stages from setting off, through picking up speed until at full gallop, the opposing troops are crushed beneath its wheels.

Cities came about as the invention of agriculture allowed for the production of surpluses, which in turn led to different classes in society. When everyone needs to farm or hunt for subsistence, these differences are small, but the growth of cities – 50,000 inhabitants or more – implies classes of rulers and ruled, of priests and craftsmen. This is exemplified in the Standard – the ruler is powerful and is deserving of tribute; he wages war so that the city may have the benefits of peace and victory.