Apparently the expression “higgledy-piggledy” is not much known in the US; my use of the phrase to an American tour group as we passed a ramshackle old house was greeted with incomprehension.

But higgledy-piggledy is the perfect description of the house at 44 Queen Anne’s Gate in Westminster, a stone’s throw from St James’s Park underground station; if you look at the photos illustrating this post you’d be hard-pressed to find a straight line that remains in the entire building.

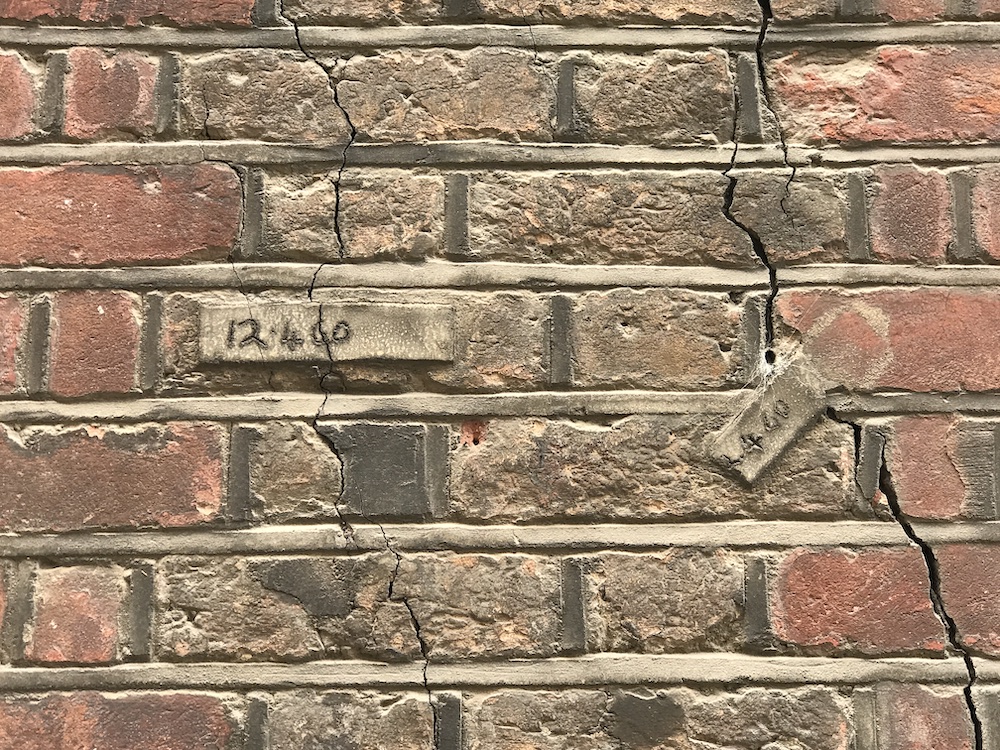

The house has been here since the first decade of the 1700s (when the street was known as Queen’s Square, the queen being Anne) and its three centuries of existence have resulted in some quite significant subsidence, with the door lintels, and window frames and sills now at a variety of interesting angles. There are even cracks down the front of the building with dated tags (12.04.60 – 12 April 1960 I presume, rather than 1860) put on by some structural engineer to check the development of the fissures (the tags have themselves cracked, showing that there has been further movement in the past 60 years).

Because of the wonders of the interwebs we can see the entry for the house in the 1926 Survey of London volume for Westminster (courtesy of British History Online), so we can read that the house is 22’ 6” wide (about 7 metres) and 35’ 9” (11m) deep. There are three storeys, plus a basement and garrets.

The Survey also tells us the occupiers of the house from its construction in 1706 through to 1840. Residents include “Lord Windsor” (this one perhaps? I’m not sure as the house doesn’t seem quite grand enough for a viscount). Then there is Sir Henry Trelawney, a Cornish baronet who was ordained as Congregationalist minister, later as an Anglican clergyman and then – aged 74 and with a wife and six children – as a Roman Catholic Priest.

Succeeding him as occupant in 1799 was the Reverend William Percy. There used to be a private chapel at 50 Queen Square (the site of 50 Queen Anne’s Gate, Basil Spence’s monumental construction that is now the Ministry of Justice) and Percy is known to have been the chaplain there in 1798, but his career is a wonderful bit of transatlanticism. Born in 1744 he was a chaplain to Lady Huntingdon, who sent him in 1772 to take charge of Bethesda college, near Savannah, Georgia. He was on the side of the colonists in the War of Independence, officiating at St Michael’s in Charleston, South Carolina from 1777-1780, before coming back to England in 1781. After his time in Queen’s Square he went back to Charleston in 1804, before returning to England (and dying) in 1819.

And in 1819 the house is occupied by James Ollier, who I believe was the junior partner in the publishing firm (the senior partner being his elder brother Charles) who were the first publishers of Keats and publishers of Shelley. As an aside, another Ollier brother – this one Joseph, a Royal Naval surgeon, lived just around the corner in Queen Street (now Old Queen Street) who features in this 1820 court report at the trial of William Marchant, Joseph’s errand boy, who was found guilty of stealing one of his master’s spoons (worth 4 shillings).

(A further aside – isn’t diving into wormholes what the internet was created for? – Joseph Ollier’s will was witnessed by one John Archer. Surely this has to be the same John Archer who is listed as number 44’s occupant in 1840?).

I don’t know who currently lives in the property (I did peek at the label on the doorbell, but unless a Mr Entryphone exists, the present resident is not naming themselves). There is no record on the Land Registry site of the house being sold in the past quarter century, but if it does come on the market at some point soon, be aware that it’s neighbour, number 42, went for £4.3 million way back in 2010.