The Tower of London Bombings

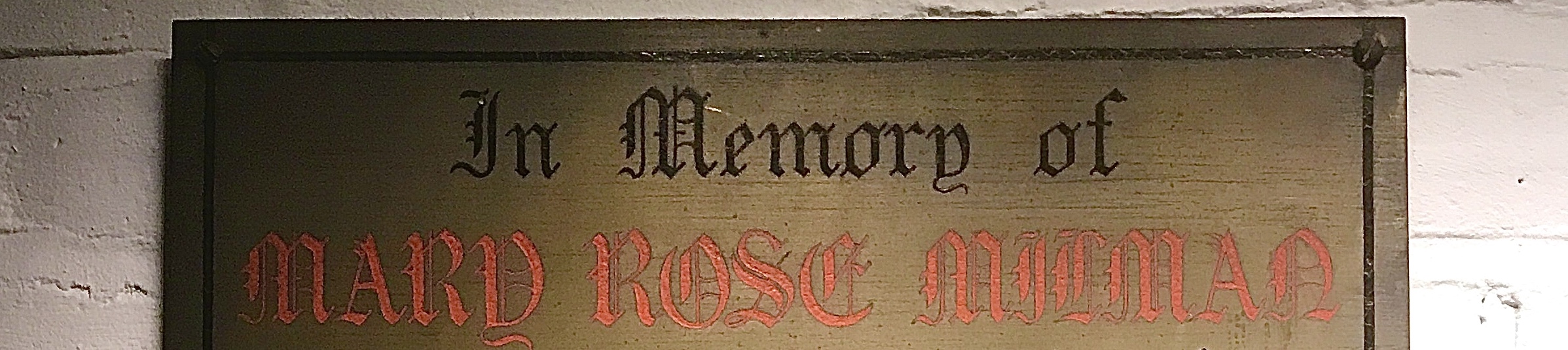

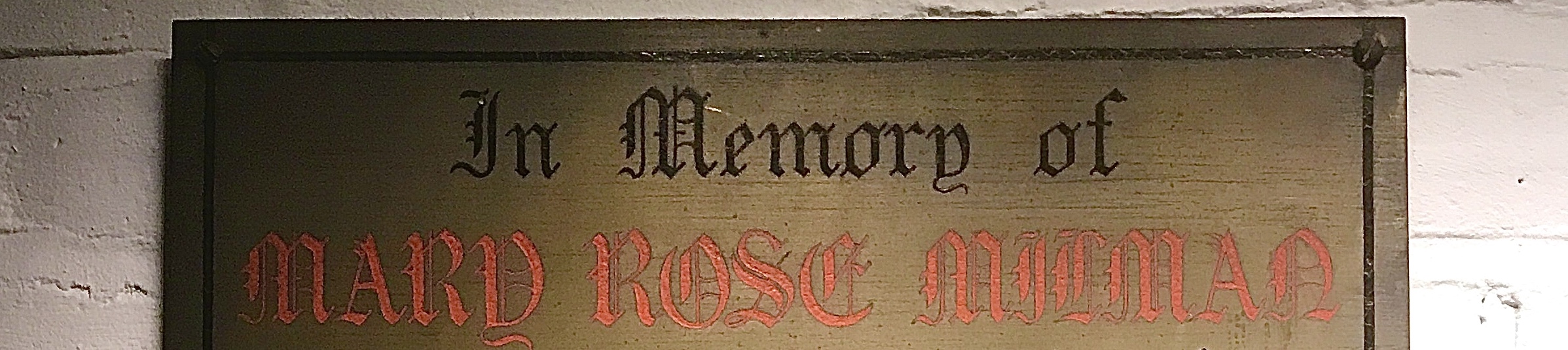

A couple of months ago I got to look in the crypt of St Peter ad Vincula (“St Peter in chains”) the Chapel Royal within […]

A couple of months ago I got to look in the crypt of St Peter ad Vincula (“St Peter in chains”) the Chapel Royal within […]

Fight your way through the crowds surrounding the Tower of London and you might just make it through to one of London’s oldest churches. All […]

You’ve probably heard of the Tower of London’s ‘Ceremony of the Keys’ that takes place just before 10pm every day. This is when the Tower […]

The Tower of London, famous though it is for prisoners, had no dungeons as such: the incarcerated would be held in rooms in different buildings […]

One of the loveliest and most peaceful spaces in London is literally in the centre of one of the busiest. The Tower of London gets […]

Just about everyone knows the legend of the Tower of London ravens; that should they leave the fortress then it and, by extension, the entire […]

Over on Kickstarter, the Thames Baths Project is within a whisker of getting its first stage of funding together to build a swimming pool on […]

Directly across the road by the Tower of London, hard by the tube station is the Tower Hill Memorial to sailors of the merchant navy […]

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes