Gebelein Man – a 5,500 year old murder mystery

One of the oldest pieces in the museum is not stone or porcelain or metal, but an actual human being – someone who walked around […]

One of the oldest pieces in the museum is not stone or porcelain or metal, but an actual human being – someone who walked around […]

One of the most famous of the early medieval exhibits from the museum is the Lewis chessmen. 93 separate pieces, in a variety of sizes, […]

The Tang dynasty – 618AD to 907AD – was one of the golden ages of China. We’re often a bit unspecific about the dates of […]

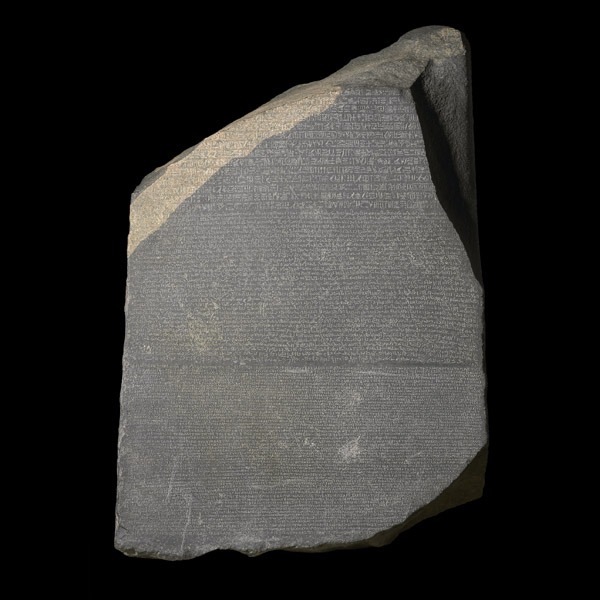

It’s a very dull piece of a granite-like stone, and the stuff that’s carved on it isn’t hugely interesting either – it’s to do with […]

You can keep your hoards of gold and silver, your Egyptian mummies, your blockbuster Viking exhibitions. For me, the most wonderful piece in the whole […]

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes