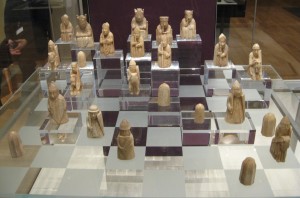

One of the most famous of the early medieval exhibits from the museum is the Lewis chessmen. 93 separate pieces, in a variety of sizes, were discovered in 1831 on the Isle of Lewis, hidden, presumably, by someone who was trading the sets. These 93 are now split between the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.

They’re exquisitely carved, with some wonderful details and are made mainly of walrus ivory – from the tusks of the walrus – with a few that are carved whales’ teeth.

[Here’s an online talk I did recently about the chess pieces]

As well as being beautiful objects, they tell us about two important things, the structure of medieval society and the nature of trade at that time.

First, trade. We said these were found on Lewis – an island to the north west of Scotland – but at that time the Isle of Lewis was part of the kingdom of Norway, which stretched from Greenland across the north to the Norwegian mainland. Greenland had been settled for its supply of walrus ivory. Remember that the norsemen were great sailors, and at that time sea journeys were generally easier than land travel, so the idea of a kingdom linked by the sea lanes is quite reasonable.

The people of Lewis would have spoken Norwegian and it was part of the diocese of the Bishop of Trondheim – and we know that Trondheim was were a lot of ivory carving was done, so that’s where these pieces may well have been created.

When it comes to how society is stratified we can also learn a lot from a chess set. Here the king is all-powerful and also must be protected. The queens at that time only moved one square diagonally – they’re now the most powerful piece on the board – and they represent the good counsel that a queen would give to her husband (in early sets, the ‘queen’ is the ‘vizier’, the adviser to the monarch).

The queens in the Lewis chess set are represented with their heads in their hands, the idea being to make them appear thoughtful. To modern eyes, though, they look incredibly bored.

Knights, the horse riding shock troops, were an important part of the king’s army, as were bishops. We think of bishops as being religious figures only, but at this time they were powerful nobles in their own right, often buying or being given a bishopric by the king. Think of William the Conqueror’s half-brother Bishop Odo, who fought at Hastings and was the most powerful noble in England.

Instead of rooks or castles, this chess set has another type of combatant – the beserker. These were fearsome norse warriors that fought in a nearly uncontrollable, trance-like fury, ignoring whatever the enemy threw at them. Here they’re depicted biting their wooden shields before they go into battle. It’s from where we get the English word ‘beserk’ – to go mad with rage.

Finally we have the pawns, and these are all anonymous; the peasants who fought for the king were looked on as expendable and don’t even merit faces. If you were a peasant in medieval society you were almost completely worthless.

Fancy a visit to the British Museum with me? You can see availability and book a private tour via Tours by Locals here.