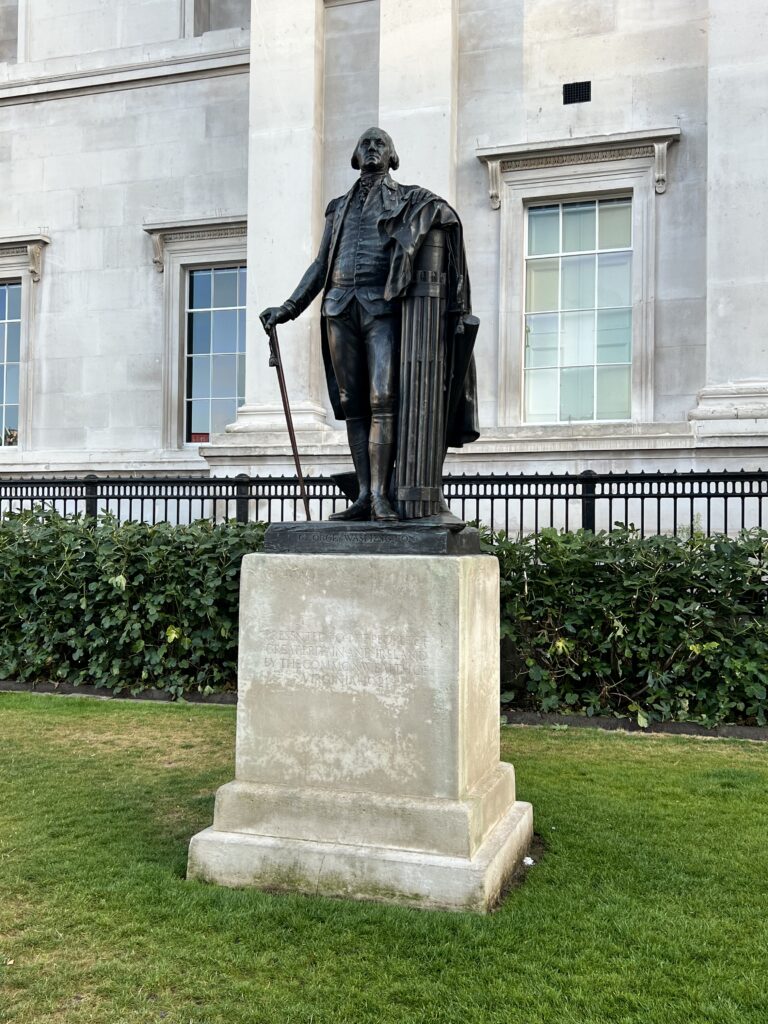

So why does a statue of colonial rebel George Washington lord it over Trafalgar Square? And why is there also a bust of the first president in St Paul’s cathedral?

(And while we’re on the subject of dead presidents, why does Abraham Lincoln face the Houses of Parliament – a recast of the famous Lincoln Park, Chicago, statue?)

One clue lies with the dates of the unveiling of each: Washington was presented by the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1921; Lincoln was a diplomatic gift in 1920; the St Paul’s bust was given by President Warren Harding and unveiled by the US Ambassador on Memorial Day in 1921.

We are therefore in the immediate post-WW1 period, when the ties of the military alliance were strong, and past, er, unpleasantness (a rebellion here, a burning of the White House there) could be consigned to history.

The Trafalgar Square statue had, though, been mooted even before the Great War, as part of the cross-atlantic celebrations that were being planned for the centenary of the 1814 Treaty of Ghent (which officially ended the War of 1812 and fixed the US and Canadian borders). The fact that UK and US troops had fought side by side in the recent war had deepened this sense of fraternalism. Witness Lord Curzon’s speech at the unveiling, where he says that the “very fact of setting up this statue here was a sign that the two great branches of the English-speaking race were now indissolubly one.” (It was Curzon who called Washington “one of the greatest Englishmen who ever lived”.) There is a very good article about the Anglo-US rapprochement here.

The statue is an exact replica in bronze of the marble original that stands in the State Legislature in Richmond, Virginia (the colonial city named after the riverside town in South West London now famous for Ted Lasso). It is by the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houbon, that was completed around 1792. The statue is life size – Houbon travelled to the US from Paris and measured Washington, as well as taking a cast of the general’s face – and as such seems small among the general oversized statuary in the square and beyond. It shows Washington in uniform, his cape and sword resting on 13 fasces (representing the original rebellious states).

There is a story that as well as providing the statue Virginia also shipped over several sacks of colonial earth for it to stand on, because Washington had vowed never to set foot on English soil. I have serious doubts about the veracity of the tale, but “when legend becomes fact, print the legend”.

(And see also the piece I wrote about the ‘great American patriot’ Benedict Arnold. There’s also my map of London memorials to Americans here.)