[Northern Broadsides production, Rose Theatre Kingston, 19-23 May 2015]

[Northern Broadsides production, Rose Theatre Kingston, 19-23 May 2015]

Shakespeare’s King Lear is one of his most powerful tragedies, with fathers estranged from the children who truly love them and betrayed by those who merely pretended to. At the end of the play the dead outnumber the living and what redemption has been achieved has been painfully and fatally bought.

Northern Broadsides’ production at Kingston’s Rose is plain and unadorned, staged by the director Jonathan Miller as if in a Jacobean court theatre with no scenery, subdued lighting, the minimum of props and with the cast wearing 17th century dress.

This almost historical staging allows Miller to draw out one of the themes that would have been most obvious to an audience of that time: that a king resigning and dividing his kingdom is an offence against God – “all nature is scourged” – from which no good could come. Miller also uses this spare setting to emphasise the personal relationships, turning the affairs of state into a family drama.

It does however make for quite a static production, putting the focus on the text and the actors. Here the stand out performance is the wonderfully named Fine Time Fontayne as the Fool, who lifts the energy on the stage whenever he appears. This is no prancing jokesmith, but a powerful and bitter truth-teller; he alone is allowed to tell the king that he is the true fool because “all thy other titles thou has given away”.

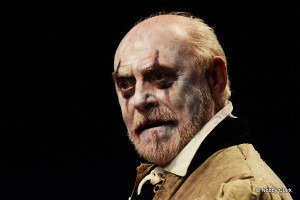

Barrie Rutter’s Lear is a vain and capricious monarch who rejects his loving daughter, banishes his wisest and truest counsellor and too late realises that the authority he had came from his title, not from himself as a man. As king he was used to getting his own way, of his subjects putting up with his rages; after abdicating, his anger gets him nowhere and in the storm on the heath, his fine robes cast aside for a simple shirt, he is defeated and downcast. Many productions have the king shouting into the face of the storm, but this Lear is subdued and depressed, his loss almost total. He seems to welcome his slide into madness and the clarity it brings, emerging broken, but considerably wiser and both more self-aware and more considerate of others.

Jonathan Miller is 80 years old, Barrie Rutter 68 and it is the older members of the cast that give the stronger performances: John Branwell as Gloucester – a touching portrayal of the portly, doltish but loyal servant to the king – who only sees the treachery of his illegitimate son Edmund after he is blinded, and Andrew Vincent’s Kent, banished for telling the king the truth. Of the younger cast members only Andy Cryer as a truly villainous Cornwall and Jos Vantyler, channelling Steve Strange as the camp and mendacious Oswald make an impression. This part is played mainly for laughs, which occasionally feels out of place as the tragedy becomes darker.

All in all this is a solid, no-frills staging of Lear, one that would perhaps work better in a smaller space that reflected the intimate nature of the production.