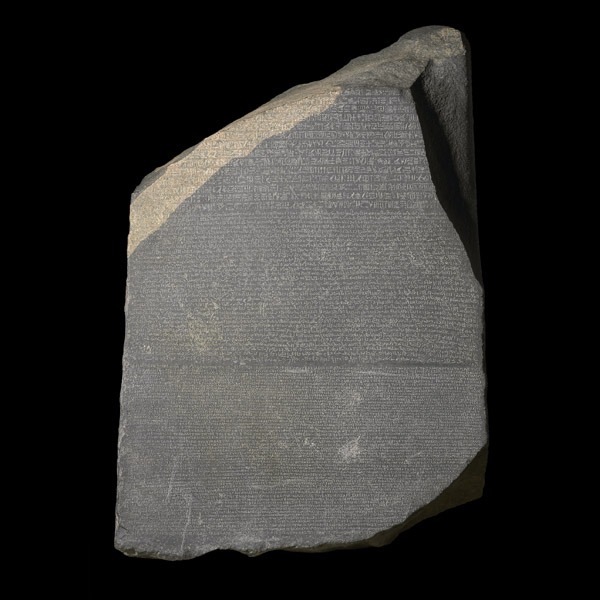

It’s a very dull piece of a granite-like stone, and the stuff that’s carved on it isn’t hugely interesting either – it’s to do with Ptolemy V, the new king of Egypt, granting tax exemptions to the priesthood. It’s not even complete – the top bit has been broken off.

So why is this the most visited object in the British Museum, buffeted by crowds sometimes ten deep, its image featuring in the British Museum shop on everything from headscarves to iPhone covers?

Because this uninspiring bit of stone – a ‘stele’ from 196BC – allowed us to decipher hieroglyphs – to understand a form of writing for the first time in over 1400 years and so unlock the secrets of ancient Egypt.

There are three scripts on the Rosetta Stone – at the bottom, Greek, the official language of the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt as the were descended from a general of Alexander the Great; demotic, the writing of everyday in Egypt; and hieroglyphs, used by the priests.

It was discovered by the French, who had invaded Egypt in 1799 as part of the Napoleonic Wars against Britain. The expedition included scholars, so when the stone was unearthed by troops – they were digging foundations for a fort near present day el-Rashid, or Rosetta as it was known – the academics deciphered the Greek which told them that the message was exactly the same in all three scripts. So they know they had something that would help them to crack the hieroglyphic code – they just didn’t know how to do it. That’s the second part of the story.

After Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1801 the French army surrendered, and as part of the surrender terms the British got all the antiquities the French had found. The Rosetta Stone was shipped back to the British Museum where copies were made and sent to scholars across Europe.

Everyone knew that the decipherment of the hieroglyphs would be a huge leap in our knowledge of ancient Egypt, and two men rose to the challenge.

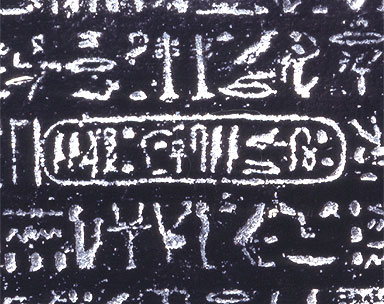

The first of these was Thomas Young, a doctor, physicist and member of the Royal Society (Young has been called ‘the last man who knew everything.). He correctly deduced that several characters on the Stone, within what’s known as a ‘cartouche’, represented the sounds of the name of Ptolemy. What he didn’t realise was that hieroglyphs were both phonetic and pictorial, with sounds and images working together. This was pieced together by a French linguistic scholar, Jean Francois Champollion, who published his translation in 1822. His complete Egyptian grammar was published after his death in 1832.

As Neil MacGregor puts it in his History of the World in 100 Objects “from then on the world could put words to the great objects of Egyptian civilisation”.

For details of my tours of the Treasures of the British Museum, click here.