As usual, it started with a bit of googling to research something completely different, but when an interesting rabbit hole appears it seems remiss not to dive straight in.

That different something was finding out about Treasury Passage, a passage (although not for the likes of you and me) that cuts through William Kent’s Treasury Building from Horseguards Parade to Downing Street. I will hopefully return to that in a subsequent post.

But while looking into that I came upon the Library of Congress’s high-res scan of John Rocque’s “Plan Of The Cities Of London And Westminster, And Borough Of Southwark, With The Contiguous Buildings” and bang went the afternoon (and much of the next morning).

This is a detailed street plan of the then extent of London started by the French-born (he was a Huguenot refugee) Rocque in 1737, engraved by John Pine, and published in 1746.

Over 24 sheets, and at a scale of 1:2400 (about 26” to the mile, or 42cm to 1km), it is fantastically detailed, and captures London just before another of its periodic growth spurts; the London of 1750 has a population of around 650,000, up 10% over the previous half-century; in the subsequent 50 years it was to grow by around 50%.

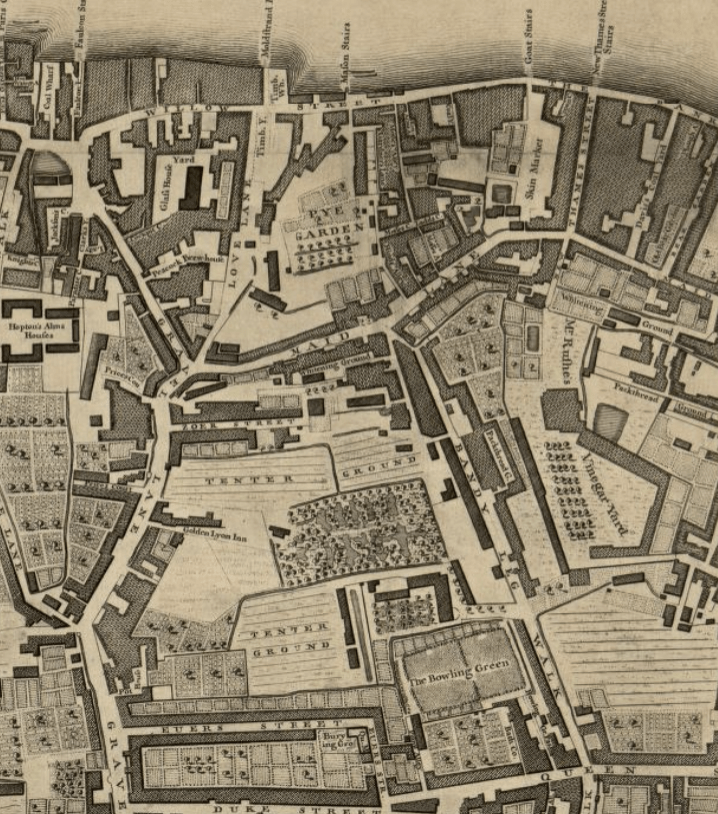

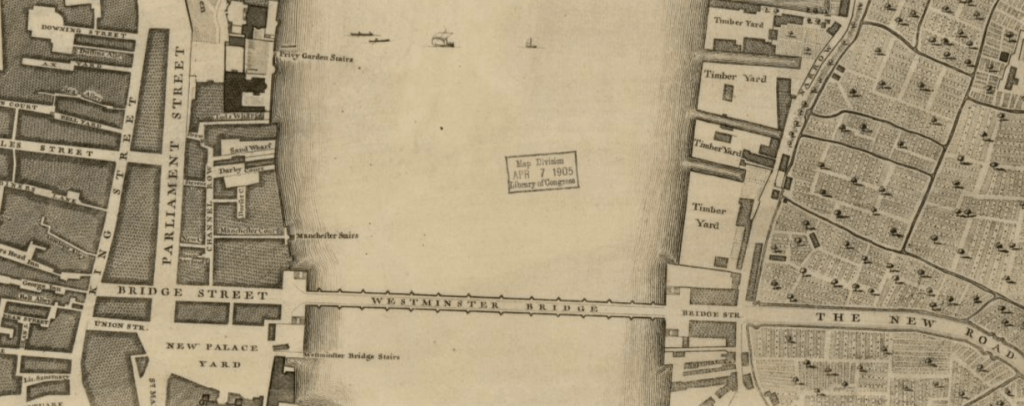

It is a much, much smaller city than ours. West to east, north to south is Hyde Park to Whitechapel, Bloomsbury Square to the river and, excepting Southwark, south of the Thames seems to be orchards, fields, ‘timber yards’ lining the banks, and lots of ‘tenter grounds’, which were areas for stretching/drying cloth (plus the intriguing space annotated as ‘ Mr Rushe’s Vinegar Ground’.)

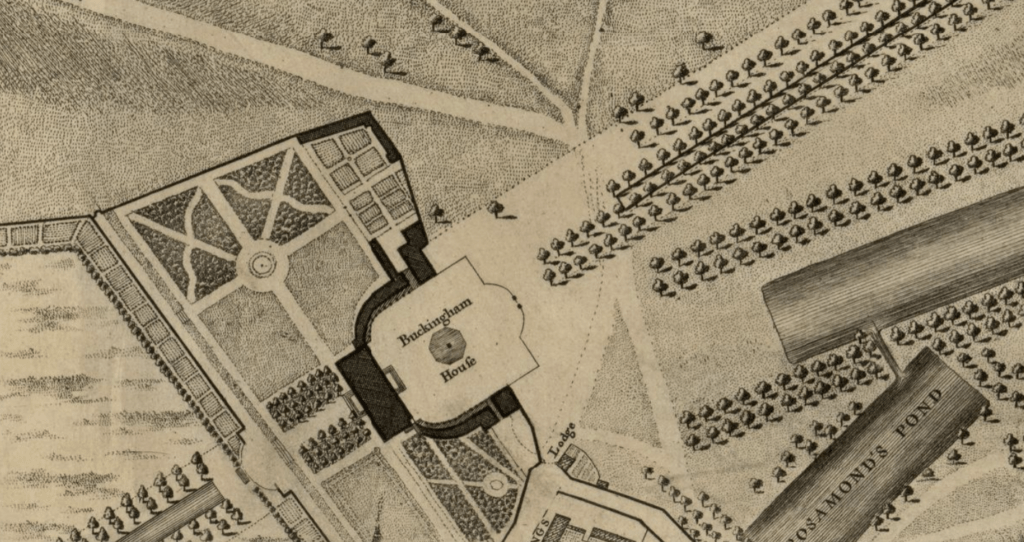

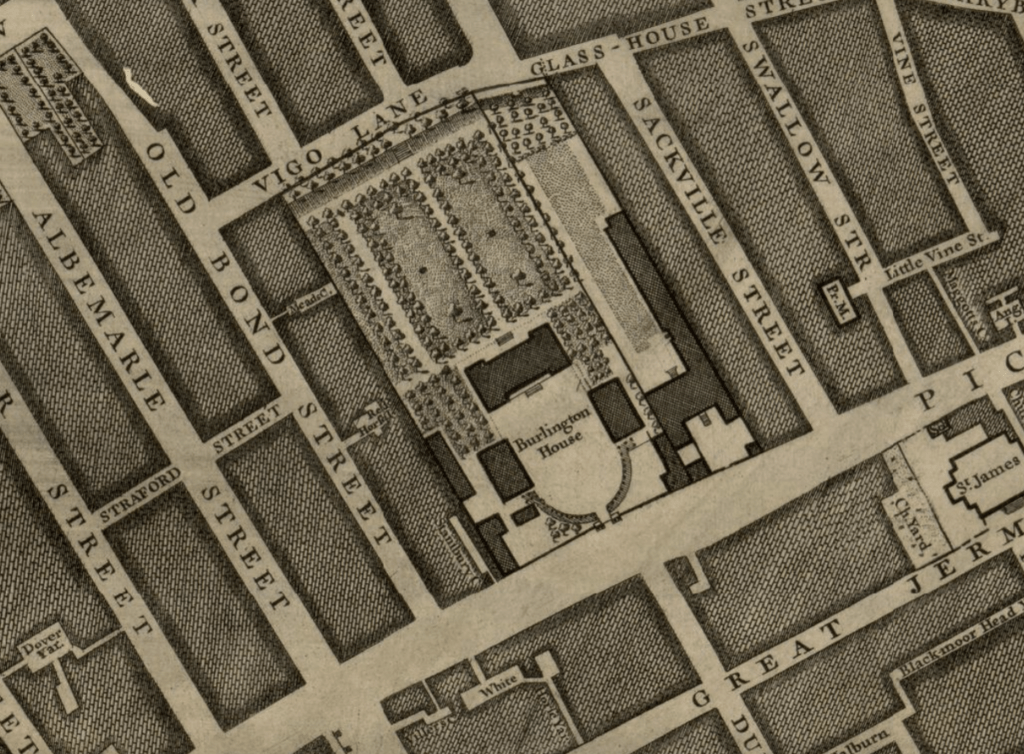

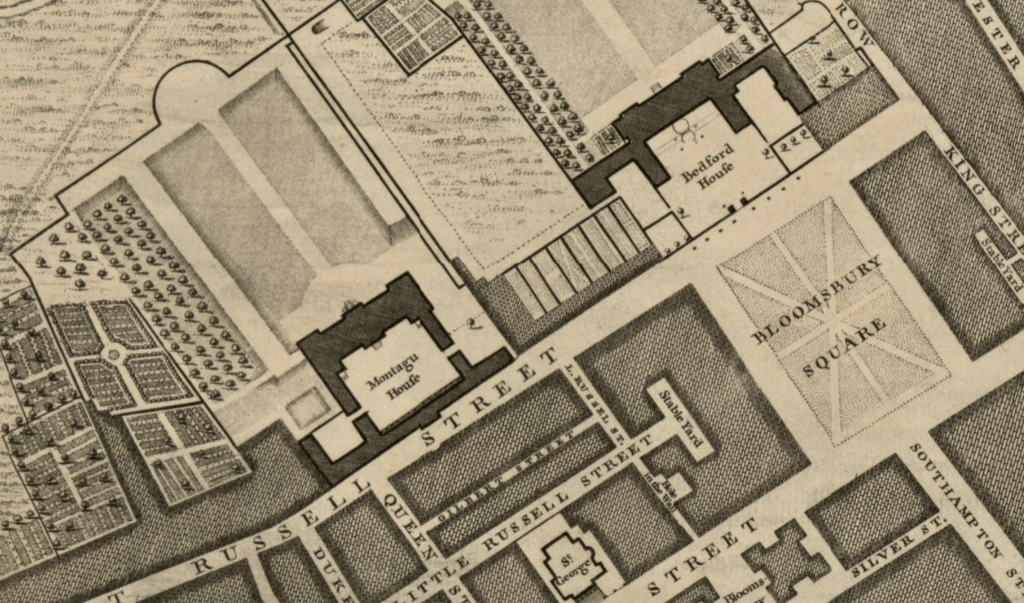

Burlington House on Piccadilly, now the home of the Royal Academy, has grounds and gardens. There is Montagu House, about to be swallowed by the growth of Bloomsbury, but still several years from becoming the British Museum. In the west, at the end of a glorious looking St James’s Park, and just before the open countryside starts, is Buckingham House – it will be another decade and a half before George III buys this property for his wife and it starts the transition to ‘The Queen’s House’ to ‘Queen’s Palace’ and thence to ‘Buckingham Palace’.

The marvellous Layers of London also have the Rocque’s map and one can overlay it on the current street map of the city, allowing an even greater level of map-based nerdery.

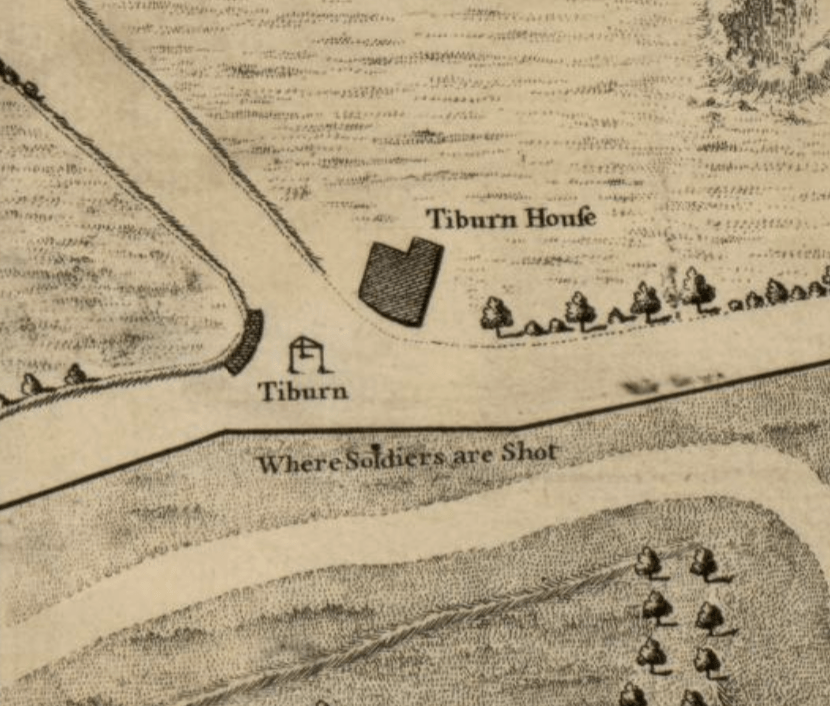

Anyway, all this is just a preamble to what caught my eye in the top left of the map. Close to the end of Oxford Street, where Edgware Road heads northwest, and where we now have that scruffy traffic island on which is marooned Nash’s Marble Arch (and where Westminster Council’s ill-starred ‘mound’ was constructed), is a drawing of the ‘Tyburn Tree’.

Marked as ‘Tiburn’ the little sketch shows a triangle supported by three posts. This is the gallows, because Tyburn was the principal execution spot for London for around 600 years, from the late 12th century. Countless thousands were hanged at this place, and Rocque’s sketch shows the wooden frame that was introduced in 1571, and which was capable (and was used) to hang up to 24 prisoners at the same time; giving, perhaps, a sense of the scale of capital punishment that existed.

Close by the tree, which Layers of London reveals is just south of the Bayswater Road, the plan bears the legend “Where Soldiers are Shot” – the punishments in the armed forces being equally murderous as in civilian life, just enacted in a different way.

Public execution continued here for another 40 years after Rocque’s map, until being moved to outside Newgate Prison (where the Old Bailey now stands) until finally being ‘moved indoors’ in 1868.

One of my favourite London facts is that one could take a tube ride to see a hanging (the Metropolitan Line opened in 1863, and it is a short walk from Farringdon to Newgate), a collision of the ‘modern’ and the ‘medieval’ that seems barely possible.