Another City church, another ancient crypt...

St Olave’s Hart Street is one of the few churches to survive the Great Fire of 1666 (it was east of the main conflagration), but its good fortune didn’t outlast the Blitz – most of the windows were blown out by a nearby bomb in 1940, and in 1941 two separate raids pretty much destroyed the place, necessitating a rebuild in the 1950s. Fortunately some of the existing 15th century fabric survived, and stone window frames could be salvaged and reinstituted into the reborn building.

But the origins of St Olave’s* are much earlier than the 15th C, as it was probably founded in the late 1000s, with a stone church built to replace the original wooden structure in the late 12th or early 13th centuries.

*(St Olave – Olaf II Haraldson – was a king of Norway who aided the English Anglo-Saxon king Ethelred the Unready in his recapturing of London from the Danes in 1014, storming Southwark and pulling down London Bridge. There are numerous nods to the saint in the City and in Southwark, including Tooley Street – a corruption of ‘St Olave’s street’.)

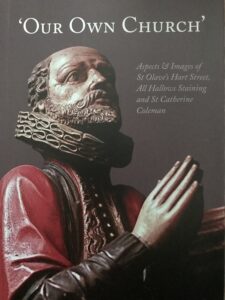

Our St Olave’s was where Pepys worshipped – he lived in nearby Seething Lane. “Our own church” he called it in his diary, and it is where he and his wife Elizabeth are buried. There are numerous wonderful Tudor and Jacobean funerary monuments and plaques, including one of Elizabeth. After her death in 1669, aged only 29, Pepys commissioned a bust of her, positioned so that it was gazing towards the pew in which he sat; Samuel could have looked into his wife’s eyes as he listened to the service.

When I went in last week I literally had the place to myself and, at the back, under the tower, found a little metal gate with a staircase leading down and a light switch. This takes one into the crypt, which dates from the end of the 12th century and which is now a chapel. Unusually, by the altar in the chapel is a well – presumably a relic of even earlier times.