If you’ve seen Herbert Mason’s photo ‘St Paul’s Survives’ – the dome of the cathedral still standing proud as the smoke of the Blitz rises on all sides – you’d be forgiven for thinking that St Paul’s came through WW2 unscathed.

Although it was relatively undamaged on the night that photo was taken (29/30 December 1940) as the City of London burnt all around it, it did suffer various attacks. In particular, on the night of 9th October 1940, a bomb hit the east end of the Cathedral, exploding in the roof and destroying the high altar and damaging the reredos (the ornamental screen) and stained glass windows behind.

Towards the end of the war the US Army Air Force (USAAF) had approached Lord Trenchard (Marshal of the RAF and Chairman of the Anglo-American Commission) to help them find a site for a memorial to the Americans based in Britain who had died during the conflict, but Trenchard had replied “it is not for you but for us to erect that memorial”.

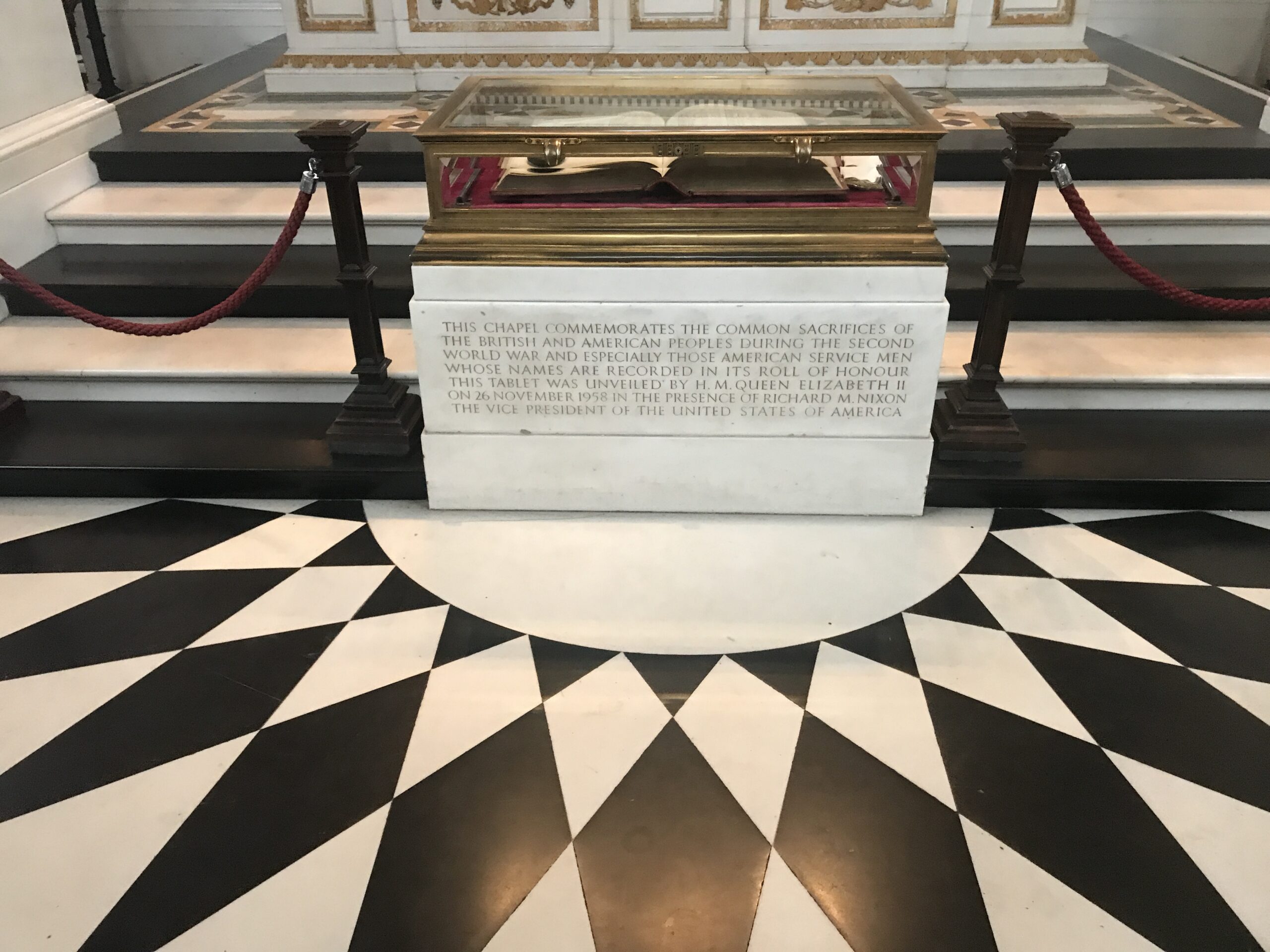

So when the rebuilding of the Cathedral was being planned post-war, the Dean of St Paul’s suggested that the space behind the high altar should be dedicated as a memorial chapel. General Eisenhower offered financial help from the US, but this was declined as it was felt that the chapel should be a tribute from the people of Britain to the Americans who had fought by their side. A national appeal was launched and the funds gathered from individual and company donations.

The new altar and chapel were dedicated in November 1958 (the day before Thanksgiving) in a service attended by HMQ and the then vice-president Richard Nixon.

The chapel is a semi-circular space in the cathedral’s apse, with the striking mosaic of Christ in Glory in the vault above. A dozen stalls are in the east of the chapel, the black and white flooring contains the five pointed ‘invasion star’ and the words “to the American dead of the Second World War from the people of Britain”.

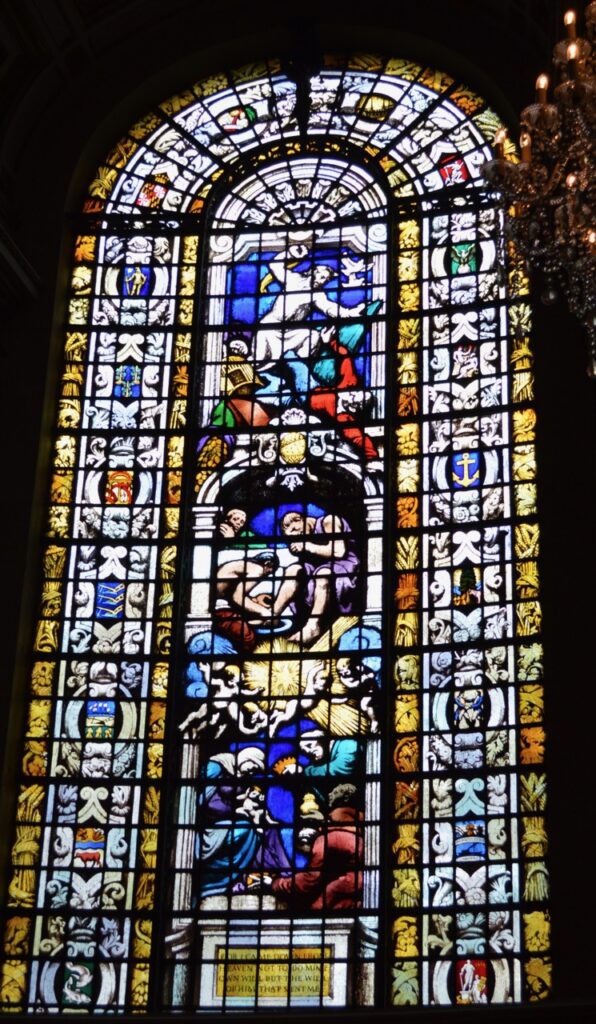

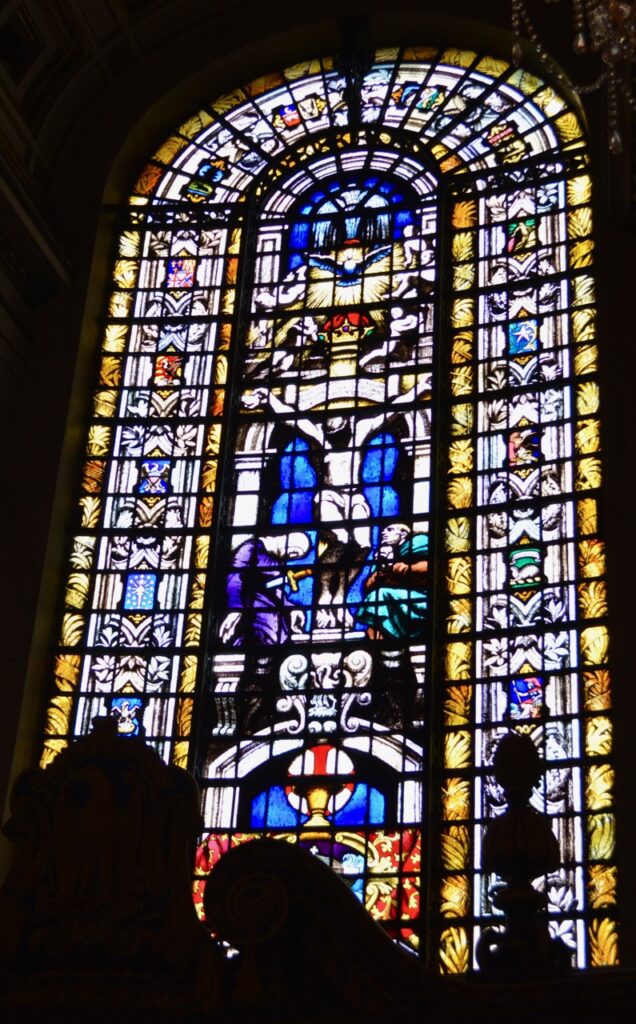

The three stained glass windows above the chapel represent “service, sacrifice and resurrection” and were designed by master glass mason Brian Thomas. In the central window, below an image of the crucifixion are the images of the Ark – a ship in stormy waters, echoing both the ships that took the colonists to north America and the passage back across the Atlantic of hundred of thousands of young men who were to take part in the liberation of Europe – and of a pelican. In medieval times it was thought that the pelican pierced its own breast so that its young could feed, it was therefore a symbol of a sacrifice made for the survival of future generations.

The borders around the main images contain the badges of the 48 states and 4 territories of the USA in existence in 1958. The stalls are decorated in carvings (echoing the wood carving of Gibbons in the Quire) of birds and flora of the States (plus, partially hidden on the south side, a carving of a space rocket – it was 1958 and the space race was just starting to get into gear).

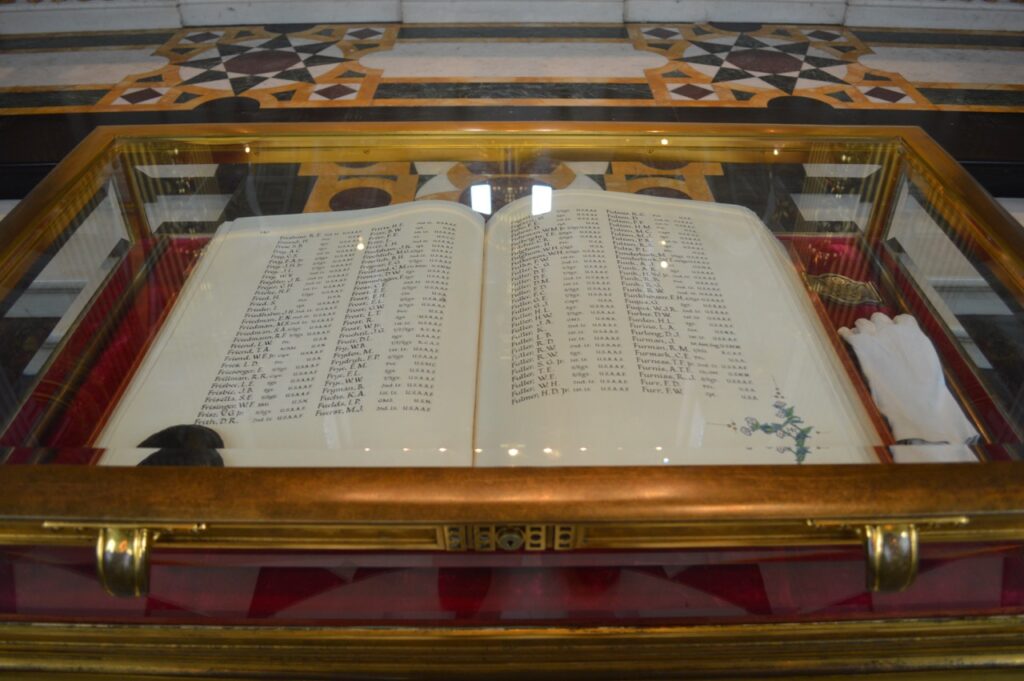

Also in the chapel is the Roll of Honor, a book of remembrance presented by the then General Eisenhower on 4 July 1951. Over 473 pages this lists the name, rank and service details of the 28,000 American servicemen based in Britain who died in WW2; each day a page is turned, a continuous process done since November 1958. (The cathedral also holds a copy of the book, for visitors who want to see the records of relatives.)

The epigraph in the Roll of Honor reads: “Defending freedom from the fierce assault of tyranny, they shared the honor and the sacrifice. Though they died before the dawn of victory their names and deed will long be remembered whereever free men live.”

To get a monthly email of my latest blog posts, just put your email in the box below.

Or follow my facebook page for London posts and photos. And I’m also on Instagram.